With Martin G. Moore

It is almost expected that when you take on a new role, you are going to find ways to do things differently, and improve the team you have. Enter the “change program”.

It is easy to get caught up in the hype… Consultants running around everywhere telling you what needs to be done, people drowning in PowerPoint decks that explain the change, and a whole facade of indicators to prove that what you are doing is working.

But how do you know if you are really getting traction? Often we take silence as a sign that everything is going well, when actually it can be quite the opposite.

In this episode we learn to interpret the noise and work out what to do with it to ensure our change initiatives actually work, rather than just believing our own bullsh!t.

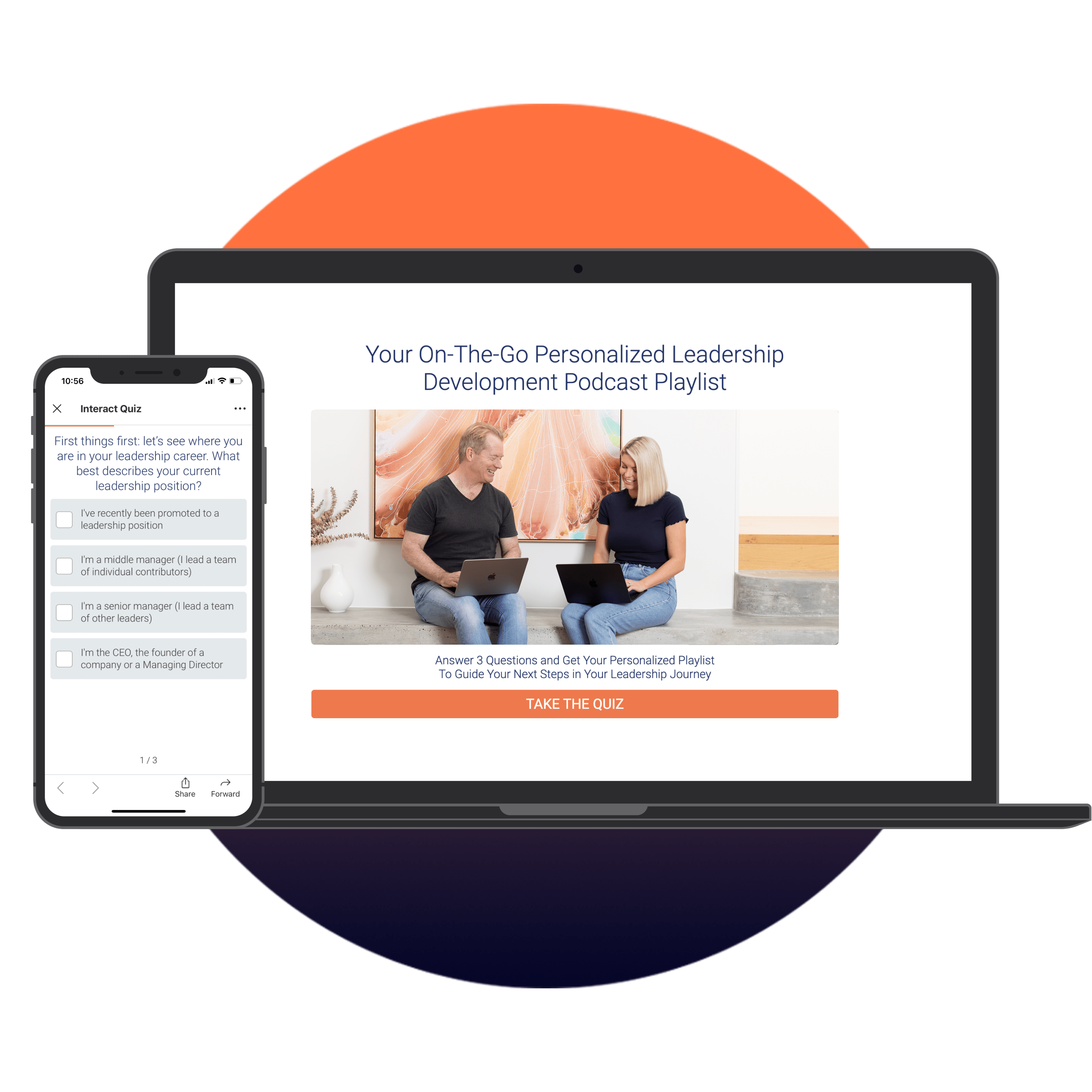

Generate Your Free

Personalized Leadership Development Podcast Playlist

As a leader, it’s essential to constantly develop and improve your leadership skills to stay ahead of the game.

That’s why I’ve created a 3-question quiz that’ll give you a free personalized podcast playlist tailored to where you are right now in your leadership career!

Take the 30-second quiz now to get your on-the-go playlist 👇

Transcript

Hey there, and welcome to episode 66 of the No Bullshit Leadership podcast. This week’s episode” No Noise = No Change: Is your change initiative really working? Most senior leaders find themselves in a position where they need to establish and execute a change or transformation program. It’s almost expected that when you take on a new role, you’re going to find ways to do things differently and improve the team you have. It’s easy to get caught up in the hype. Consultants running around everywhere, telling you what needs to be done, people drowning in PowerPoint decks that explain the change, and a whole facade of indicators to prove that what you’re doing is working. But there is really only one indicator that you need to monitor, to understand what the real level of progress is. How much pushback are you getting from the old guard who loved the world the way it was, before you turned up?

We’ll start by considering the typical types of change initiatives that organisations embark upon, and why they often fail. We’ll talk about why people push back and why this is a good thing, and we’ll finish with some classic examples of how people push back and why you should welcome, rather than avoid these. So, let’s get into it.

Hey guys, I just want to quickly jump in and let you know that we have officially opened pre-registration for our online leadership program, Leadership Beyond the Theory. Now, for those of you who are new to the podcast, Leadership Beyond the Theory is our7-week online leadership program that unlocks the secrets of true leadership success. We only run two cohorts a year, it is tried and tested. We’ve had hundreds of leaders from all over the world complete the program with incredible feedback and results. So, if you’re serious about improving your leadership capability, quality, and confidence in 2020, head to www.yourceomentor.com/preregister, and jump onboard. Doors will open for enrollment on Monday the 20th of January, with class starting on Monday the 3rd of February. Head to the Leadership Beyond the Theory page for more information on the content, program outcomes, links to past student case studies, and all our FAQs. That’s at courses.yourceomentor.com. Alright, back to the episode.

Now, before we kick off, if you haven’t noticed, No Bullsh!t Leadership has a big change theme going on, and this is just one in a series of these types of topics. So, in last week’s episode, we spoke about the capacity of individuals to change and what your accountability is, as a leader, to help them do so. But it’s definitely worth going back and listening to a couple of episodes that we’ve had this year. So, episode 46 was called ‘The People Who Built The House Can’t Renovate It‘, and episode 56 was called ‘Dealing With Change Resistance: You Will Need To Shoot A Hostage.’ Now, it’s just purely coincidental that 46, 56, and 66 deal with change. I wish I’d planned it that way. Anyhow, let’s get going.

Let’s start with the typical types of change initiatives that organisations embark upon and why they often fail. New leaders in new roles want to make change, for the most part. There is always an expectation that there are things that can be done better and the team can be taken to another level from where they’re operating at the moment. Change initiatives come in all shapes and sizes, and I’ve been involved in heaps of them over the years. So, of course, there’s your classic ‘strategic transformation’. And this term covers a lot of ground. Even transformations that aren’t particularly strategic are often labelled with the word strategic because it sounds so much cooler and more important. But a strategic transformation normally signals a change in direction for the organisation. In other words, “We’re going to fundamentally do things differently. We may get into new products or new markets or new customer segments.” And often, these arise as a reaction to competitive or industry forces.

Then, there are the restructures. Now, these are normally really expensive and really disruptive, but unless layers of people are being effectively removed, and of course the essential work that they did is not being ignored, these restructures rarely yield benefits.

Then, you have commercial reforms. And commercial reforms actually come with a fair degree of success. You’re looking for better outcomes for investment and returns, so things like inventory rationalisation, capital productivity initiatives, procurement and supplier reform, all of these things can yield good longterm benefits.

Of course, the holy grail is culture change, and that’s the trendy one right now. The catch cry of every board and CEO, from New York to Geneva to Auckland, is that ‘we are changing culture’. It’s the trickiest to execute, and it’s the hardest to measure because it has a really long tail.

Almost all of these change initiatives follow certain patents, so very often, they start with a consultant who comes in to review the organisation. Now, we’re told that we need to change and there’s nothing wrong with this. It’s not necessarily a bad idea. And we look outside for comparison because competition is external to us, not internal, for the most part. We devise a plan for change, and then we work out how we’re going to communicate that change to the troops. And of course, everyone gets onboard with this. The PowerPoint decks start coming out, the glossy brochures are produced, and the impassioned speeches that go on with our people. But I’ve got to tell you, they simply don’t cut it. These are normally long on justification, so that you can sell the change to the troops, but short what’s expected and required to make the change successful.

So, embedding and understanding the will and the tools to change, in the layers of leadership below you, is the tough bit. But many leaders believe their own bullshit. They listen to what their people say. Watch their feet, not their lips. And leaders completely underestimate the capacity of the organisation to protect itself, particularly if there are some long standing bad habits. Now, I talk about the white blood cells that swarm around to protect the body from a foreign organism, and sometimes when you come in as a leader, with an agenda for change, that’s exactly what happens. The white blood cells try and protect the existing organism and to kill the threat. But we completely underestimate the inability or unwillingness, of some leaders below us, to make that change.

With all these types of change initiative, there are some common sticking points. The first is what I like to call the change sugar hit. Initial results are achieved, but once the impetus and momentum of the change program diminish, it’s not embedded and everyone goes back to business as usual. And this is really insidious, as you can think that something has changed, when it actually hasn’t. People have just ridden through the project piece and done what they were told to do, while under extreme scrutiny. The second sticking point, hidden cost. Now, restructures are particularly prevalent with this. They cost a fortune, and probably only a fraction of the actual cost is physically counted. So, the obvious things like consultants and additional external resources and so forth, but the things that had never counted in a restructure are the human toll, the loss of productivity before, during, and after, and inappropriate attribution of results further down the track, to the actual restructure itself. Now, I’m a massive believer in the axiom that any structure works, self-evidently. You can see that any structure works because organisations go through restructure after restructure, and the results still come through.

The third sticking point is strategy without execution capability. Now, most organisations have a reasonably logical strategy, but these strategies tend to fall apart in two places. Firstly, in the assumptions and choices that are made in going through the strategic planning process, and more commonly, in execution. And execution normally fails because of poor leadership. Now, a great quote from General Norman Schwarzkopf, who said, “Leadership is a potent combination of strategy and character, but if you must be without one, be without the strategy.”

Why do good people push back and why is this a good thing? First of all, there’s a change in the status quo. People are moving from what’s familiar and comfortable to what is unfamiliar and uncomfortable. The moving from what is known to what is unknown. So for example, there can be changing power dynamics. Leadership may have more say in the future, in what goes on and what gets done. There may be a drive to eliminate poor conduct or behaviour. So, bad habits may have been formed in the organisation over a really long period of time. Unwritten rules, for example, being paid overtime payments for work that should be done in standard hours. And of course, these people are smart. They can see the writing on the wall. If we’re more productive, we won’t be asked to work extra hours, and we take a hit to our pay packet. And then, there are just cultural norms that creep in over time, knocking off early on a Friday afternoon, three hours early to go for drinks. Sometimes, people are just being pushed out of their comfort zone, so they’re working harder, or worse, they’re having to be held accountable for the results they achieve.

Sometimes, they’re changes that may be contrary to people’s belief systems. Now, this is one you have to really watch out for. For example, I have had leaders in the past, who I know have a belief that everyone should have a job, regardless of what they do, how they behave, or how they perform, the job is their entitlement. But this makes a job, and of course an organisation, simply an extension of the unemployment benefit system. Sometimes, changes move people from focusing on rights and entitlements, and they make that shift to accountabilities and responsibility. So, why is it a good thing that these people push back? Well, number one, it confirms the fact that you’re doing something different. When you get pushback, it tells you that people are resisting the change. When you don’t get pushback, it tells you that people aren’t concerned, and they have no need to push back because everything is going on exactly as it always has.

The second reason why it’s a good thing to get this pushback, is it will alert you if you are actually doing anything stupid. And just occasionally, there are actually really good reasons why you shouldn’t push ahead with a certain part of the change. If you don’t get the noise, you’re never going to find that out. Now, I do know leaders who say to themselves, when there’s no noise around the change and everyone’s saying, “What a great idea, boss,” they think to themselves, “Wow, I’m such an awesome leader. Look at how well constructed this change program is. It must be fantastic because everyone agrees with it and we’re all going ahead into nirvana together.” I hate to say it, but that’s just pure bullshit. It just means that you haven’t looked at the realistic possibility that there’s no pushback because there is no change.

Let’s finish with some classic examples of how people push back and how to handle them. And these are all from bitter experience, I have the scars to show. The first example I have is on passive aggressive avoidance. Now, I had a situation a number of years ago, where I asked for one of my direct reports, a senior leader I’d inherited, who’d been in the organisation for some time, to commence a project for me. He listened carefully, he took notes, he nodded and smiled. And he walked out saying, “Sure boss, no problem.” Now, things just went quiet for a while. So, a few weeks later, I asked how things were going. Once again, smiled and nodded, “Yeah, yeah. Yeah, good boss, all on track.” But I just had this nagging feeling. I hadn’t seen any requests for resources, there was no inclusion, in the reporting regime, for the list of work programs and so forth. It was just all a little bit too quiet. So, a week or so later, I pushed harder and said, “Show me what you’ve done and where you’re up to. I want to see the outputs from your planning so far.” What I got back, I could not have been more shocked. He said, “Well, we’ve decided not to do that, and here’s why we haven’t done anything because it never would have worked anyway.” Like dude, seriously? No noise, no change.

The second example is one of direct defiance. So, once again, I had an acting general manager, and she’d been in the organisation for quite some time. Now, I was trying to establish the level of capability and competence in the leadership layers below her, and I think there were probably four or five layers in this case. What I asked for was a ranking of the leadership capability, on the whole. So, let me know who are the pick of the bunch, who are solid performers as leaders, and who simply isn’t cutting it. Basically, she resisted this request directly, I guess thinking that the weight of numbers and solidarity from her leadership team would eventually wear me down and I’d get tired of it and go away. She obviously didn’t know me very well, hadn’t worked with me for very long.

So, she insisted on the following answers, and I chased this up three or four times. “There are no superstars and there are no underperformers. They are all just solid, decent performers. Every single leader I have, all the same, all solid, nothing to see here, boss.” This was the noise I needed to see. If I hadn’t pushed, I wouldn’t have got any visibility of that, and no change would have happened with that General Manager. It wasn’t until I created the near mutiny, though, that I heard the noise that told me that change was imminent. Needless to say, the General Manager didn’t survive beyond lunchtime.

The third example is that sometimes the noise is just a little too obvious. In one organisation I came into as an executive, the labour unions ran a very targeted campaign against me. They spread all sorts of rumours about my intention, how I was rewarded, what my targets were for reduction of staff numbers, and so forth, and they spread these very surreptitiously, eyeball to eyeball, with the troops. Then, on top of that, they were printing outrageous lies in their weekly newsletter. Every single week, right in the shit sheet, there I was front and centre. Now, my first instinct was to commence legal action for defamation and slander, but then I realised this was actually the best indication that the change I was driving was actually meaningful and had the potential to genuinely change the way people worked. It was not my intention to relieve these people of their secure, well-paid, and undemanding jobs. But I did expect that when they turned up, they were going to work for a living, so I turned this resistance into a sort of KPI.

For me, this was an indication that I was right on track. As soon as the heat died down, I knew it would mean one of two things. Either the perceived threat was nullified or better still, the changes were being made and people were realising that the world wasn’t ending, the sky wasn’t falling, and that there were positive aspects to the change. Without that fierce pushback at the start, though, from a workforce that had spent decades successfully resisting change, it would have been a sure sign that there was either no likelihood of change taking place, or that the change was not reaching the bulk of the workforce because the leaders between me and them was simply stifling it.

There is one tricky bit here, mental health issues. Now, mental health issues seem to be becoming much more prevalent, and it’s not clear to me whether they were always there and are now just being spoken about and recognised more, or if there’s also a genuine lift in the number of cases. This is why a leader has to know her people so well. And I’m talking, specifically, about your direct reports. So, this means that leaders right through the line, bear that responsibility for their direct reports. You get to know your people by stretching them, by challenging them, and by seeing how they react. You get a sense for the level of resilience any individual has, and if they’re struggling emotionally, you should be able to recognise it. But guess what? This means that you have to have a reasonable emotional intelligence.

There are three common scenarios here, but very, very many shades. So, scenario one, you don’t know the person well enough to be able to see where they are at, and you carry on regardless. In case you hadn’t realised, this is bad. The second common scenario is that you recognise that something’s wrong and you say, “Well, I guess that’s it. I better not push them, so I’ll lower the standard for Sarah.” This is also really bad because all of a sudden, for no apparent reason to the people around you, you’re just setting a lower standard for the team. But the third, and probably the best scenario here, is you actually speak to the individual about getting help. You refer them to a professional who’s qualified to deal with these issues, and you support them with the space and time to work through any issues they have. This may mean reassigning them to less stressful work for a period of time, while they’re working through the problems.

To tie all this up, as a leader, you need to welcome the noise. This is the truest indicator that something is working and people are becoming uncomfortable. You’re not trying to make people unhappy, but if everyone is comfortable and complacent, no one’s world will ever be any better.

Alright, so that brings us to the end of episode 66. Thanks so much for joining us, and remember, at Your CEO Mentor, our purpose is to improve the quality of leaders globally, so please share the podcast with another leader whom you know will benefit. I look forward to next week’s episode, Simplicity and Focus.

Until then I know you’ll take every opportunity you can to be a No Bullsh!t Leader.

And guys, don’t forget to preregister for Leadership Beyond the Theory at courses.yourceomentor.com. If you love this podcast, you are absolutely going to love the program and get so much value out of it, so I really encourage you to go and check it out. Alright, we’ll see you next week.

RESOURCES AND RELATED TOPICS:

Explore other podcast episodes – Here

Take our FREE Level Up Leadership Masterclass – Start now

Leadership Beyond the Theory- Learn More

YOUR SUPPORT MATTERS

Here’s how you can make a difference:

Subscribe to the No Bullsh!t Leadership podcast

Leave us a review on Apple Podcasts

Repost this episode to your social media

Share your favourite episodes with your leadership network

Tag us in your next post and use the hashtag #nobsleadership